How to Write a Play

Here, you'll find a step-by-step guide on how to write a play. For more creative writing tips and inspiration, join our writers' email group.

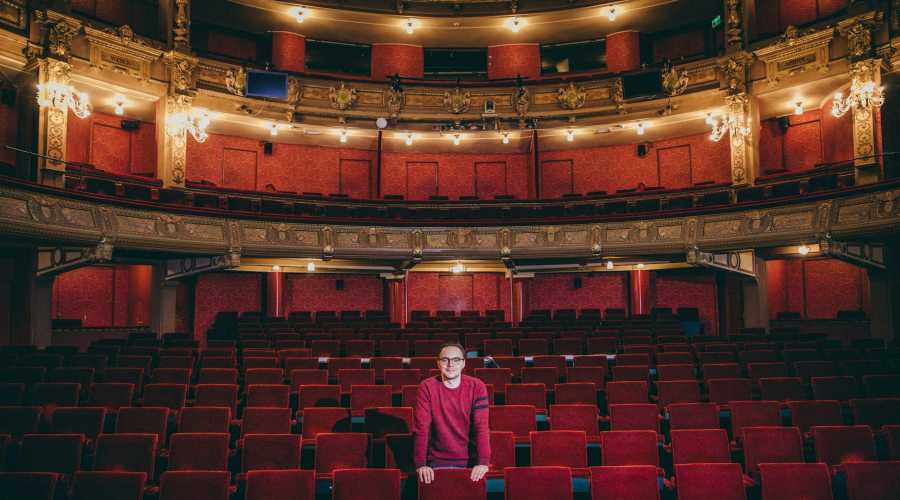

Imagine the thrill of watching your words come to life on the stage... Imagine sitting in the audience and watching other people laugh and cry at the actions of characters you've invented...

Even if you've never written a play before, you can learn to do it! And you can find ways to get your plays produced—if not on Broadway, then in community theaters, schools, churches, festivals, or other local venues.

How to Write a Play - Skip to Topic

- Immerse yourself in the craft.

- Come up with a character.

- Decide on a conflict.

- Choose a starting point.

- Show the story in action and speech.

- Pare it down.

- Write and rewrite.

- More on how to write a play.

Immerse yourself in the craft.

To learn about playwriting, it's important both to read other people's plays and watch them in performance.

It can be especially helpful to watch the same plays many times. The first time you watch the play, you experience it as an audience member, but several times through, you can analyze it more objectively, noticing aspects of the playwright's technique, as well as observing audience reactions.

If you're interested in writing plays, it's probably because you want them to actually be performed. Therefore, you'll need to take into account the practical aspects of producing a play. A play with live tigers on the stage and seventeen set changes is likely to cause some production challenges! To learn more about what's involved in a theater production, volunteer at a local theater if you can or find some other way to get backstage and watch how things actually work. This is also a way to make interesting contacts in the local theater community who can give you feedback on your play and can eventually help you get it produced.

Come up with a character.

One way to get ideas for your play is to start with a character. Who is your play about?

Your character might be based on a combination of real people you know. Another good strategy is people-watching. Invent lives for people you see in in the supermarket or at the mall. What do you think their names might be? What kinds of homes and jobs do you imagine for them? What do you think is the most urgent problem that each person has to deal with?

Writing character profiles can help you imagine your characters more fully.

Decide on a conflict.

Your play should have a conflict. Give your character a major problem that they have to solve immediately.

Why? Why stir up trouble? why can't you leave your poor character in peace?

If everything's perfect in your character's life, then nothing has to happen. Happiness is very nice to experience, but it's boring to watch. There's a reason why "Happily ever after" comes at the story's end. Cinderella and her Prince Charming wake up late, eat a nice breakfast, and take a little walk. Good for them. But no one would buy tickets to see the play.

It would be different if it were...

- "Happily ever after, except for one extramarital affair and its violent ending..."

- "Happily ever after until Cinderella discovered Prince Charming's secret dungeon..."

Think about the character you have invented. What's something this character desperately wants? What difficulties might get in the way? There's a conflict for you.

Decide on a beginning point.

Let's say our play is about Prince Charming's extramarital affair. What's the best place to start it?

- Prince Charming's birth.

- The first time Charming lays eyes on his future lover, a chambermaid named - Petunia.

- Charming and Petunia's first kiss.

- When Cinderella walks in on Petunia and Charming in bed.

- When Cinderella stabs Charming and Petunia to death and throws their bodies into the moat.

If we were writing a script for a movie instead of a play, we might choose the fifth option. The film opens with a crocodile peeling Charming's crown off his head, much as you might remove a scrap of foil wrapper from a bonbon, before taking a luscious bite. Then the movie flashes back to show a shocked audience the story of how Charming ended up in this state, Prince Charming's tragic transformation from eye candy to crocodile candy.

It's harder to flash back like that in a play. Movies and novels can jump around almost effortlessly in time and place, but such transitions become more complicated in the theater, where live actors are performing on a stage. Plays therefore often take on a shorter period of time. If we were writing a thousand-page novel with all the time in the world, we might begin with Charming's birth, his childhood, his first love, Mimi... But this is a play, not a novel, and we have a limited time to hold the audience's attention.

What's the most exciting point in our story? Probably when Cinderella stabs Charming and Petunia to death. This is the story climax, the moment when the story's conflict reaches a peak. You can think of the climax as a decisive battle which determines how the story will end. After the climax comes the resolution, when the dust settles and the audience gets a glimpse of the result -- the crocodile munching on its treat, Cinderella moving her summer clothes into Charming's half of the closet...

If we start our play at the climax, the audience will be lost. They'll see a crazed princess storming into a bedroom, but they won't know who she is or why they should care. There will be no built-up tension, no suspense, just a bloodbath in the royal bed. And the play will be over almost as soon as it has begun.

Instead, what many playwrights do is to start the play a little bit before the climax. The play begins with a situation that has a lot of tension already built up. Charming and Petunia have been messing around for months and now are plotting to poison Cinderella's soup. Cinderella has noticed that Charming's been less charming than usual and wants the Fairy Godmother to spy on him. The play begins. Tensions are already high. Tempers are short. The situation is explosive. And the audience gets to watch it all blow up.

Show the story in actions and speech.

"A silent tear rolls down Cinderella's cheek as she pulls a long black hair off Charming's pillow. Thoughts of murder burn in her mind as she tosses the hair into the fireplace. Two years ago, when she caught the Prince behind the barn with a milkmaid, he promised that he would never stray again. She believed him then, but she won't be betrayed a second time."

Sure, but a theater audience can't see any of that.

What do they see? Cinderella leans over the pillow, then walks over to the fire and holds out her hand.

They can't see the silent tear.

They certainly can't see a single black hair.

They don't know what thoughts or memories are in her head.

This isn't a movie, where the camera can zoom in. And this isn't a novel, where the narrator can describe the character's thoughts or fill in background information (some plays do have narrators, but I don't recommend using this option, which can seem old-fashioned nowadays).

Instead of a hair, we could have Cinderella find Petunia's nightgown. Not very subtle, but at least the audience could see it.

Or instead of crying silently, we could have her call the fairy godmother into the room and tell her about the hair. By turning Cinderella's discovery and thoughts into speech, we let the audience in on them.

As a playwright, your main tools are speech and actions (and by actions, I mean ones that the audience can see from the back of the theater). Is Prince Charming a nymphomaniac? Is Cinderella a ruthless social climber who will trample anyone in her path? Think about what words and actions will let the audience know. Is Cinderella becoming suspicious? Is Charming plotting to get rid of her? Show it with words and actions.

Pare it down.

Should we give Cinderella's stepsisters a little part in the play? Bring in the Prince's friends? The royal army? Should we add a subplot with an attack on the palace from a neighboring kingdom?

Let's think twice before we complicate things too much. Instead, we should be trying to simplify, to pare things down.

If our play contains too many moving parts, it's going to be harder for us, the playwrights, to manage everything successfully. Having too many characters, costume changes, and scene changes can also make the play more expensive and difficult to produce.

Write and rewrite.

Some writers spend months or even years developing ideas, jotting down notes, writing character profiles, brainstorming. They like to know where they're headed before beginning. Others write as a form of exploration, discovering the path as they go. Once they see where they end up, they start a second draft, and maybe more drafts, revising until they get it all right.

There is no single approach to writing that works for everyone. But some general advice:

1) Read and watch lots of plays if you want to write them.

2) Write regularly, even if you don't feel inspired. If you sit down every morning at eight o'clock to write, sooner or later, the inspiration will come. On the other hand, if you wait for inspiration before so much as picking up a pen, you might have a very long wait.

3) Don't expect your first draft to be your final one. Things almost never come out perfectly on the first try. So don't be scared by the blank page. Write down something. Then come back and improve it.

Reading your dialogue out loud will help you hear where revision is needed. Are there places that sound unnatural? Conversations that move too slowly? Parts that will be difficult for an actor to pronounce or an audience to understand?

If you are following the first piece of advice and reading a lot of plays, then you have a general idea of what a script looks like. But be aware that the formatting of published plays is a bit different from the formatting you should use for your script. You can find a detailed guide to script format on the playwright Jon Dorf's website, Playwriting 101.

Or, you can use a software application to format it. Celtx and Story Architect are two options with free plans that will help you format a play.

How to Write a Play - Next Steps

Join our free email group for more writing help and inspiration.

For a complete guide to how to write a play, check out Louis E. Catron's book, The Elements of Playwriting.

You'll find resources and information for professional playwrights on the Dramatists Guild of America website.

More articles on how to write a play or screenplay