Karl Elder on Language Poetry and More

Poet Karl Elder spoke with us about language poetry, the "sense in nonsense," poetry's metaphysical dimension, and the nature of poetic inspiration. You can read our conversation below.

Karl Elder is the author of nine collections of poetry, including Gilgamesh at the Bellagio, Phobophobia, A Man in Pieces, The Geocryptogrammatist's Pocket Compendium of the United States, The Minimalist's How-to Handbook, and Mead: Twenty-six Abecedariums. His poetry has won a Pushcart Prize and other awards and has been featured in the Best American Poetry Series.

A Conversation with Karl Elder

Creative Writing Now: In an essay published on the Wisconsin Humanities Council website, you have criticized language poetry and the "aesthetic of chance." To what do you attribute the popularity of this aesthetic?

Karl Elder: It’s difficult work, trying to be innovative (I’ve said it elsewhere: a poem is a poem, in part, because it’s unlike any other poem) and anticipating the needs of an audience (even if the audience shall consist solely of the poet’s own ears), and I believe there are far too many public displays of attempts made with half a heart, there being so much psychic energy required. I actually had two aesthetic modes in mind when I wrote the remark to which your question refers, and I suppose I yoked them in the essay because I view both as passive, the poet like a weathervane, pointing without will, wherever the wind wants. It may be that, as Wallace Stevens said, the true subject of poetry is poetry, but it sure as shot is not simply language, nor is that noble endeavor, the poem, governed by luck. In the grand scheme of the universe, human beings choose or die; they exercise volition, assuming they’re grownups. On another scale, so do poets.

Now, on the other hand, when Marcel Duchamp laid a urinal on its back and called it art, it was art. Some of what made Duchamp an important artist is that he had sense not to overdo it, except when reinforcing for a time his divinely minimalist concept of “readymades.” But for my mind there’s no way that concept has the power of, for example, his painting called Nude Descending a Staircase, which is far from self-referential, unlike language poetry. Language poetry, in general, is like all other language poetry; it’s not so much abstract as it is failure of the poet to abstract. As art, poetry is founded not upon technique—rock-solid or not—but upon multi-layered platforms, such as human experience, role-playing, the number of associations and depth of emotion the chosen words “in the right order” have the power to evoke, etc. There’s not a whole heck of a lot of emotion induced from staring at an algebraic formula, which is flatly a symbol of a function sans values.

Your question tempted me at first to explain my aversion to both language poetry and the aesthetics of chance by using the analogy of the hive—workers and queen. (Oh, the buzzing from one direction and the drone in another!) But that trope won’t soap, that picture won’t develop, except to convey that, in order to realize potential, a poet must become her own boss as well as be industrious—obsessed, in fact.

Ok, so think factory: a maker (the poet) climbs from labor to management. She needs a variety of experience—janitor, foreman, quality control inspector, forklift operator, sweeper, production accountant, say—in order to be the best she can be. If she passively accepts her station on the line, she has capitulated to chance while not having a gossamer-garbed angel’s chance in hell of controlling her own fate. (Uh, by the way, I’m not what one might call a feminist; I’m an egalitarian libertarian who can’t stand among other ills the morally corrupt notion that all art is equal in stature.) And if you’d care for a contemporary example outside the realm of poetry of my kind of angel, complete with a spiritual compass (that in the case of her story wobbles, there being no true North) and of what I believe to be great art, see the film Winter’s Bone. It’s a hero’s lesson in heroism, but it speaks masterfully of an intangible reality made real—and I’m not talking about the illusion of film or “the magic of movie making”—through tangible imagery. “Reality is only the base,” Stevens also said. “But it is the base.”

Imagine playing draw poker and standing pat with each hand. Eventually you’d be saying, “What happened to my chips?” Later, but not much later, you lose.

Creative Writing Now: In the same essay, you refer to the value of the irrational in poetry, when used correctly -- when it is "the right kind of crazy." Could you talk more about this? Could you talk about the role of play, wordplay, humor, serendipity in your poetry?

Karl Elder: So that following a mid-day trip my wife and I do not have a crabby grandchild on our hands, in order to keep him, a three-year-old, awake in his car seat, I sing his favorite songs, but with a twist: Old MacDonald had a farm—G.I., G.I. Joe. “NOOOO,” he guffaws and then giggles, meaning, of course, “That’s irrational.” Children seem to know intuitively that whacky language is not crazy so much as it is craziness, and should they happen to grow into contemplative adults, craziness may become, for instance, something as serious and challenging as the irrationality of The Book of Job, subject the poem is to interpretation that the divine is revealed only in questions for which there are no answers. Another thought—paradox is a form of irrationality; nevertheless, we “understand” it. And once upon a long time, it was irrational to speak of the earth as round. Yet how prompt our conversion. Human evolution has well outfitted the brain for sea change in an ocean of eons to come, we hope.

Revisiting my Poetry Daily essay, “The Sense in Nonsense,” I see that it speaks sparingly not of the “right” kind of crazy in poems but the “good” kind. The difference in my mind is such that I have little to say about the “good”—it being subject to taste—while I welcome a chance here to explore the “right” kind of crazy in poets themselves. I’m moved (perhaps due to that psychological phenomenon known as projection) to view said behavior as compulsive, though hardly neurotic, especially when I think of “strangeness” as a common characteristic of the finest literature I’ve encountered.

Derived from my own habits, for example, is a semi-conscious refusal to break from a state of awe, drawn to the shy mask of the universe, and I’m not talking about star-gazing necessarily, though, heaven knows, I’ve spent a lot of time behind our two-story house, using it to block a street light, with toilet paper tubes for binoculars. The cardboard works remarkably well to impede peripheral illumination, enhancing the contrast: a studded, concave, black pincushion overhead mostly obscured by the tops of birch, basswood, ash, and a monstrous, hydra-like, 300-years-old oak—the trees’ leaves also of help as, gradually, my dilating pupils multiply the number of stars, magnifying the depth—felt turning into velour and, eventually, velvet.

Should I happen to have been revising on those nights—I hesitate to say “composing” because I spend so little time with initial drafts relative to the ensuing work—I invariably take my cerebral toys and their backdrop of celestial afterimages to bed with me, often dead tired, a zombie’s insomnia self-induced. It’s quite a mild state of paranoia, I suppose, in that the awe about which I speak previously is not that I feel diminished; no, it’s ongoing ontological wonder manifest in myriad scenarios, how it is that one’s consciousness, being such a magnanimous gift, so huge relative to awareness in an owl, say, or a mouse, or a mite, is squandered—in that a life, subjectively and objectively speaking, is but a flicker in the dark, a tick in time.

While the edge of sleep may serve like a lab where the bare text of poetry is conjured, serendipity, the fortuitous melding of associations, occurs in wakefulness. One does not play well half asleep. Neither does one there willfully crack jokes, an engaging ancillary thought being that humor (and surely wit) has come to be observed by neuroscientists as stimulating attentiveness in others. No wonder the greatest theory of poetry out of the twentieth century of which I’m aware, The Necessary Angel, surfaced from the watchful mind of a poet with tremendous affinity for comedy, though Stevens, even at his most jubilant moments, is hardly what one might these days call LOL. After all, the direction he took is a path in deep shade, if not darkness, that all serious poets must enter: the future and its name, whether it be bad or good, for there is no poetry if there is nothing to push through or back against, and that includes in the most fundamental sense the blank page. “Remember,” I sometimes address students along with myself, “poets were the original fictionists.” We know all about fiction—no friction, no fiction—and though it may not appear to be so on the surface, a poem’s gestation being more mysterious, there is always tension (sometimes both obvious and latent) in the poem, precipitated by tension in the mind that makes the poem, no matter how small or how menacing or how pleasant the emotion. As an illustration of what I mean by tension, here’s one of my own very early poems, a piece in celebration, a tribute, whatever surprise therein being, I must admit, the mildest bit of wit:

Snowplow

for W.C.W.

The blade

scrapes sparks.

How unlike

the snow.

Now, because my work has evolved through modes progressively more formal and expansive than that of the little piece above, far be it from me to serve as a channel for reductionism in order to echo the illustration, but while I was typing “Snowplow,” one of my students, Ben Endres, as if the muse’s messenger, dropped off with two other pieces for next week’s workshop his

One Line Poem

This is not

one of those

Maybe Ben’s been in my office when I was showing-off my inscribed copy of William Matthews’s An Oar in the Old Water. Looking like an elongated book of matches, it includes

Premature Ejaculation

I’m sorry this poem’s already finished.

Surely at this moment even the most priggish reader of “Premature Ejaculation” wears, at the very least, a residual smile. If not, one would think that among this essay’s audience is the next thing to a robot. Still, there are degrees of appreciation in response to tension in poetry and, thus, to this poem. If a reader has a vocabulary extensive enough to perceive the double meaning in ejaculation (the word like a sterile anti-pun in the context of “premature” shifting to an ante-pun when the piece is done), he or she sees and is quickly seized by even more tautly-wound tension. That’s what wordplay can earn a poet and his or her audience—a lingering, reserved seriousness in the midst of wonder at the power of language, for which in the long run is a life become incrementally rich.

Suddenly I’m reminded of Dorothy Parker’s response in a game to use on the spot the word horticulture, creatively, in a sentence: “You can lead a horticulture, but you can’t make her think.” Likewise, you, the poet, can do only so much. An editor once wrote that she was able to discern some of the wordplay in a long poem of mine only after having proofread it several times. Almost reflexively, perhaps in defense of the intense labor poured into that poem, came a hint of irritation, but with an empty can of tomato soup in my hand, I experienced her remark as a boon—no bane: “She understands that instead of water you prepared it with milk, Elder.” Besides, a poet must take heart; I mean, while there is no wire to trip the trigger in a reader’s head, one has control over infinitely more important joy to be had, and that is the quality act of dwelling at play itself.

Creative Writing Now: In an essay in the Beloit Poetry Journal Forum, you describe poems as multi-dimensional art objects -- although a poem exists in two dimensions on the page, you explain, it has another, metaphysical, dimension. Could you further describe this metaphysical dimension? How might it differ in poetry from prose?

Karl Elder: Here’s the most important portion of that to which you refer, I see:

- I sometimes think of poems as possessing both an ecto- and an endo- skeleton—the latter metaphysical—poetry then seemingly a phenomenon as much like sculpture as painting. Oh, it’s two-dimensional on paper, all right, but multi-dimensional in the formulation and in its readers’ apprehension of that latent energy before them.

To conceive of “the poem” as a two dimensional art object, similar to a painting or photograph, as I imagine, for example, some of William Carlos Williams’ short work invokes in young or inexperienced readers of poetry—despite W.C.W.’s famous reference to poems as “machines made of words”—is to see what is possible in poetry (its power to affect in the most sublime sense) sucked through a vanishing point like a trashed screen on an iPhone. A problem I have with Williams, by the way, is his insistence upon adherence to idiom. It’s not that it’s impossible to make poems with common language; the trouble is that vernacular is comparatively static. Should one dwell on that frequency, hearing how stuff is said rather than testing how it may be said with verve, there’s tendency to become a chronicler or recorder at the expense of innovation and, from the point of view of one’s audience, of the opportunity to see in stereo. I mean, let’s face it, offshoots of the mode in question—the list poem, for instance, though it may embody refrain as a legitimate technique that serves as a superstructure—are inherently inferior subgenres simply because they are relatively shy of imagination. I sense irony in all of this. Williams is universally considered left of center on the spectrum, leaning heavily toward a more “democratic” poem, while his nemesis, the poet whose “elitist” poetry he despised, T. S. Eliot, is, aesthetically speaking, retrospectively and in fact, the true progressive by way of craft.

The mind of the generator as well as the beholder of good poetry dwells at the center of concentric circles, each of 360 degrees infinitely divisible. A trope more applicable to the finest work might be that the mind operates as if it sits dead center of a sphere with an exponentially infinite number of points encompassing it. When I think of the greatest poems I’ve encountered, I think of the poems themselves, impossible that it is to explain their effect for as much as a nanosecond. Attempts to identify the power of such a poem by uncovering the poet’s tools, thingamajigs or stratagems, are degenerative and futile, like squinting at gold to see the atoms. On the other hand, one can capture for a time what masterpoems have in common. We know that when the piece is read holistically, the effect is real but unstable and, in a sense, undulating: one moment, say, a cube in a sphere and, in the next, a sphere in a cube. Maybe a wordless poem would serve here just as well to explain what in perpetuity can’t be explained. How about one called “Metaphysical Cubism”?

If poetry is like chess, prose is like checkers. Now, I’m not disparaging prose; never once did I defeat my maternal grandfather, the man after whom I am named, at checkers. Yet, in the act of composing this very sentence as well as in recollection of writing prose—essays, short stories, and two novels—I am aware that for the sake of my own satisfaction prose is a mere anteroom to the palatial interiors, a yet-to-be uncovered cave in all its glistening passageways. Often the initial draft of a poem is cast in prose, I concede, but the poet in me wants more than the writer in me can deliver.

Yes, when you’ve been to the mountaintop, no matter how briefly, having experienced its rarified air, poetry is like chess, prose is like checkers. Literary theorists of the early part of the last century talked of the difference between practical language and poetic devices, both of which are integrated into the poem. There’s an obvious difference in their function, prose being subservient, a means to an end, while the devices serve as ends in themselves—arresting a reader, making progress difficult not for difficulty’s sake but to spawn new perception. A most memorable compliment I received as a poet came only a couple of years ago from my mentor of forty years—Lucien Stryk. Responding in a letter to my The Minimalist’s How-to Handbook, he wrote, “Karl, you see things no one has ever seen before.” It’s not what I’ve seen that’s important to me ultimately; it’s the fact that I’ve seen them and that the will to do so potentially serves as a model and perhaps even inspiration for others to realize their capacity for unique perception and a richer imagination. As I said in an interview a few years ago,

- Hearing [poetry], reading it, and creating it are all exercise for development of the imagination. Now, so are other arts and endeavors. But there are none that are either as portable or as efficient as poetry because of its inherent characteristic that requires of the forebrain to make its own pictures in order to experience it, which partially explains poetry’s ubiquitousness among the species, especially with respect to education of the child and the necessity of passing the baton—cultural myths—from generation to generation. And what is education if not an attempt to equip persons with imagination and experience for the sake of the capacity to anticipate, to solve problems of survival on one hand and, on the other, to make a life worth living? That which has arrived to make us the dominant species on earth, imagination, the ability to see into the future and thereby avert threats to our existence, comes hand in hand with the curse of the knowledge of our own demise. As for the poet, his or her role in such a scheme is therefore adaptive, ranging from the voice of an angel to the canary in the mine. The poet’s responsibility is the will to sing.

Now, I have neither the gift, skill, nor inclination to engage in the kind of observation necessary for a direct benefit to mankind, like—allow me to be hyperbolic here—cures for disease or its psychological corollary, dis-ease. But as to the idea that poets do not directly affect the world—and in contrast to the great prose writer and aesthetician Walter Pater, who believes “. . . art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake[,]” and in spite of what I believe to be Pater’s enormous influence not only on the likes of Wilde but, subsequently, Pound, Eliot, Stevens (maybe even Williams [and certainly diminutive me])—strikes me as false, particularly when we’re talking about superlatively wrought poetry, which is positively dependent upon observation to then join normally disparate elements to reveal the intangible behind the veil of reality. Call me a neo-aesthete or dandy any day, but I would hope that what is clearly evident in my work is penchant for the metaphysical.

There’s good reason why so many poets are struck by John Donne and his ilk. Those seventeenth century English bards, with more passion than most moderns, appropriated with a passion what the students of Aristotle hammered out as being the central quality of poetry in The Poetics (only recently did I discover it was not Aristotle alone who produced what we refer to as his theory)—metaphor or, more specifically, thanks to the inventiveness of the old masters in question, conceit. Whatever the trope, a seasoned reader intuitively understands that what transports him or her to a higher plane of consciousness is wrapped in sentience. Assuming familiarity with the language in which the art object is cast, be it that which is material or abstract but a thing experienced in space through time, and excluding incantatory effect via repetition, there needs be brevity, hyper efficiency of language, which by its nature facilitates perception. Why, then, are shorter poems not more valuable than longer ones? It is for the same reason that there is inherent in language types of trope—from symbol or icon (barely temporal) to conceit (temporal)—meaning there are facets of reality and/or experience which require more time to render and to apprehend than others. It is an understanding such as this that points to the difference between poetry and prose. Both are valuable in that they serve different temperaments and moods. It’s just that the truly well-off among the world know the human spends life not in dollars and cents but in minutes and moments.

Back to the importance of sentience, however, effect, and the expansion of imagination and consciousness—it is the prose writer’s obligation to tell, to inform, even to instruct, but it is the poet’s charge to suggest. It’s the difference between Ayn Rand and Howard Roark. The poet would rather work like Roark than like Rand. The poet would rather make than talk, addressing the right and left lobes of the brain rather than the left alone.

Creative Writing Now: In a discussion in the Beloit Poetry Journal Forum, you comment on the nature of poetic inspiration, saying that "even sudden insight is apparent to me to be the result of preparation." What conscious steps can poets take to prepare themselves for these moments of insight?

Every burgeoning, serious poet wants to know how to write his or her best work. The method is perhaps absurdly straightforward. “Make ready for your gifts. Prepare. Prepare,” said Ted—Roethke, that is. What is not revealed by way of that brief admonition is how long and involved the lessons can be, how arduous the labor.

Allow me to invoke the mother of all fundamentals, no matter the preferred genre: the art of writing is inherently a moral endeavor. It is value laden; it is a product of a person’s capacity to care—not to emote as much as to coldly pay homage to the art form in its ability, ultimately, to affect.

Granted, there are levels of caring, of this love. There is infatuation; then there is courtship. The more mature this love, the higher the quality of writing the maker is capable of. Hence, a lovely and entirely rational paradox is painstakingly born in the mind of the writer. The novice slows down, becomes familiar with the tedium of learning the mechanical and grammatical conventions of the language in order to speed up perception in anticipation of the needs of an audience. That Frost dictum, “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader,” is only the bottomrung of the ladder or—should one prefer a more romantic trope—base camp for the climb.

What writers call sudden insight, though analogous to spontaneity, is only an illusion of it. Yes, the fuel, a cache of language, must be present to ignite. Experience, the oxygen, appears to be invisible in the way that the subconscious, though lurking, is cloaked. Desire is the heat, the degree of value, energy amassing through irretrievable time.

Where from then comes the value and thereby the will? It’s easier to first imagine how the will may be sustained—a philosopher’s stone, a refuge of habit and reinforcement forged by what I sometimes whimsically call a “plintany”: probing, praise, publication, performance, and the prodding that comes from plenty of envy. Envy? You bet, I can think of no better word—pride’s nemesis, that has its source having been exposed to greatness: Shakespeare, Milton, Dante, Donne, Keats, Emerson, Thoreau, Poe, Twain, Hawthorne, Dickinson, Melville, Lincoln, Eliot, Frost, Stevens (by all means Stevens with his theory of poetry), to name idols who immediately come to mind.

Despite that as a kid I belonged to an organization for which its motto is “Be prepared,” despite that the Boy Scouts of America provided me with a real-world education comparable to none (to explain might require a memoir), despite years of writing poems, for which I had only earnestly begun at the age of 21—four decades of my life had passed before I realized the formula for my own best work, which required from me patience and consciously engaging in a kind of inventory. Following answers to what subsequently seemed rather obvious questions (what do I truly have knowledge about? what is the character of that which stirs me when I read?), I fell upon this question: besides being pretty decent with words, what else can I do? As circumstance would have it, birth order played a role in my answer.

Here’s a little riddle: how, among five siblings, is it possible for a youth to have been the youngest, the middle child, and the oldest?

A half-brother 16 years my senior, one of three Teds ricocheting like amusement park bumper cars in my head as I write (my father also known as a Ted) returned from the Korean War to work on a master’s degree in education on the G.I. Bill. He needed a subject—my half-sister being unavailable and my other two siblings too young—in order for him to gain experience at administering two types of tests—interest inventory and spatial relationships (the latter requiring the mind to manipulate two-dimensional patterns into 3-D objects).

The results of the interest inventory suggested that because of a liking for science and literature, I ought to pursue becoming a technical writer. Yet, it was the spatial relationships test that proved to be the eye opener, although I did not fully awaken to the implications for many years.

“No, no,” my much older brother said when I’d completed that second test and tried to hand it to him, “you don’t just guess at the answers. You have to figure out which answer is right according to the pictures.” It seemed that I’d completed the test in fifteen minutes, about one third of the time allotted.

“I didn’t guess,” I said, and I remember him staring into my eyes for about five seconds.

Well, there on the airy front porch of the big old rented house at 222 Elm Street in Leland, Illinois, did I watch Ted convert raw score into percentile, unimpressed was I that my performance ranked in the 99th or that I had answered nearly all items correctly—not impressed, perhaps, because the test contained neither words nor numbers and because my 6th grade teacher, whose house I could see from where I sat, only a block away, knew better than I that I was horrible at word problems. Algebra, I subsequently came to understand, is not my forte. Geometry was.

All of this is to say it is an amalgamation of luck, inclination, reading, steady work, and introspection that a map to a personal masterpiece might be drawn. Of course, I would be totally remiss not to point specifically to the piece that launched me to a higher plane of endeavor, so I beg from you your endurance, believing that it is best for the sake of answering what “conscious steps” are possible to summon insight to first describe the primordial soup from which the poem in question emerged.

As for luck, it can be good, bad, or—perhaps more importantly—both. Take a look at what I’m suggesting by considering this account of my early experience with haiku that appears in the online Verse Wisconsin article"Encyclopedia of Wisconsin Forms and Formalists" edited by Michael Kriesel.As one who has experienced first-hand Japanese culture for twenty-some months in succession, I’m not sure I or any Westerner is blessed with the perspective necessary in order to be able to write genuine haiku. In fact, following my stay—courtesy of Uncle Sam—I used to write rejection letters as the editor of Seems which rather arrogantly expressed my doubt. Then one day it hit me: while I might not be able to capture the true spirit of haiku, who’s to say a poet on this side of the Pacific can’t write poems containing 17 syllables? I suppose you might call my pitiful epiphany a turning point in my career in that I’ve since composed scores of 17 syllable poems (yes, in three lines of five and seven and five syllables)—almost all bearing a title, which is a no-no to a master practitioner of haiku, of course. On the other hand, I wonder if it’s reasonable to think that a Japanese poet could make what I make in English. My good fortune at having had over the years a couple dozen native speakers of Japanese in my poetry writing courses (Lakeland has a 2-year associate of arts degree program in Tokyo from which native speakers of Japanese often transfer to Wisconsin to complete a bachelor’s degree) reinforces my doubt—not that those students can’t write in English (many have been remarkable); it’s just that the idioms that surface in their poems lend the work the indelible mark of the rising sun. Ask a Japanese student what the rooster says or what the pig says or what the cow says, for example, and, upon hearing a response, you’re liable to conclude for the moment that—rather than different continents—you were reared on different planets.

When I think of how an artist is aesthetically inclined, I imagine a fusion of predisposition (meaning kinds of intelligence that dominant his or her mien [see Howard Gardner]), temperament, and metabolism, all three of which are pretty much out of the maker’s control. Still, it is self-awareness (intrapersonal intelligence?) of talent—in my case spatial intelligence—that allows me, I believe, to conjure pictures from stark abstractions, a twist on Wallace Stevens’s definition of poetry as “making the invisible visible,” and to blaze my own path through the trees to the elevation at which I’m able to glimpse the top of the mountain.

Now, what is absolutely in control of the poet, a conscious step without which having taken it again and again I would have been thwarted on the climb, is the choice to attentively read, open to suggestion and influence. Among thousands of periodicals, books, and manuscripts, my jealousy at the degree of pleasure particular poems stirred in me became, if not the catalyst, the impetus for my determination—whether I’ve accomplished it or not—to add, in whatever small measure, to the canon. I can point with some certainty to at least four experiences in my extended career of reading that spurred in me—more than mere admiration—the envy of which I earlier speak, all moments alike with respect to the intensity of my response: “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” portions of Coleman Barks’s “Body Poems” that I first encountered in Geof Hewitt’s Quickly Aging Here (1969), James Merrill’s Divine Comedies, and an image from the hand of Billy Collins.

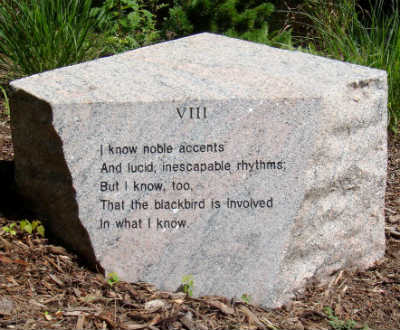

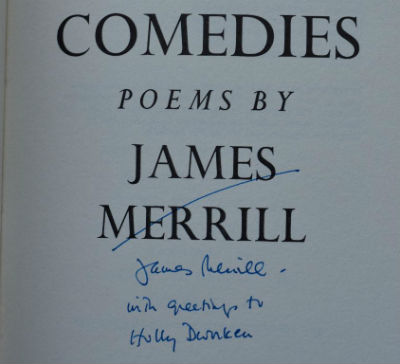

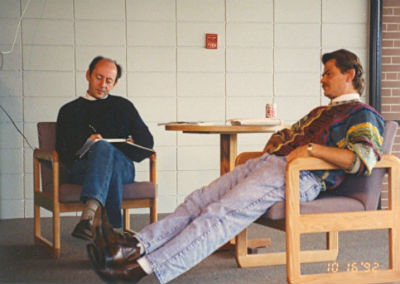

Retrospectively, it is no wonder to me that I’ve made a pilgrimage to Stevens’ gravesite on the anniversary of his death [See Photo 1 below] as well as walked the Stevens Walk [Photo 2], the thirteen ways chiseled in granite markers on the route from his home to the Hartford Insurance building [Photo 3]; that a few years ago I sought out and now own the Barks book, The Juice (1972), containing the complete “Body Poems”; that I possess an inscribed first edition of Divine Comedies [Photo 4] (with Merrill’s inked-in corrections!); and that, according to Collins, who revealed the following fact to a pair of my students, I am the first person ever to have bought him a plane ticket, back in 1992, when he served as a featured writer at the Great Lakes Writers Festival, which I continue to coordinate [Photo 5].

What else but envy?

Yet envy alone is not enough, of course. Neither is desire become manifest in the company of those whose work one esteems highly nor is bibliophilia. One values what poetry has to offer to the degree of intensity at which one is moved to work, when the “stars” eventually align, so to speak. Then there is that ascent toward perfection, knowing full well that, fleeting, perfection recedes by gradually smaller fractions in the process of gaining upon it. At last there arrives confirmation that being able to contribute to the canon is merely penultimate in importance—after all, one’s selection for inclusion in any hall of fame is completely in the hands the future—but most important is that the quality of the work, achieved by having become a devoted practitioner of the art form, stands as tribute to that which is a link to its own lineage. Surely my parents would have been pleased to know that I understood this principle even before I encountered it as a graduate student in Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” To put it plainly, one strives to do one’s best out of respect.

So here come the details of how I learned to pay homage, having paid my dues through 20 years of apprenticeship and the muse, that ungrateful tart, suddenly having lost my name on her muster:

I heard one winter, that winter,on a PBS program that Richard Wright, whose Native Son I’d closely studied and taught, had, toward the end of his life in an artists’ colony, abandoned prose for poetry, which he wrote daily, his medium being haiku. “Heck,” I remember saying, sitting up, “I can do that.” And, despite a considerable bit of luck at maintaining the pace, hell it became, tired as I was after months of staring at the moon.

Still, I added to the stack, an index card per day, until it appeared that I’d cornered boredom so that it was ready to bite back, and I abruptly recoiled. Shortly thereafter surfaced the three questions identified above: What do I truly have knowledge about? What is the character of that which stirs me when I read? Besides being pretty decent with words, what else can I do?

I’d dabbled in black and white photography in my twenties, and it occurred to me now that the most memorable images I’d shot were essentially geometrical. And I’d always loved billiards, the innumerable possibilities the sport affords, those spheres on a rectangular bed of felt stretched tight over slate from which it is heaven to create when a player, having practiced its fundamentals, becomes proficient enough at the game, able to control where the cue ball rests. “Shape” is what that is called and what I was after bent over the table. Could writing be analogous to just staring at the object ball until stuff like where to apply English on the cue ball, at what angle to hold the cue relative to the slate, and the speed of the stroke became second nature?

Suddenly I’m not writing a haiku a day. I’d become wide-eyed at the letter A as I’d scrawled it on my 3 x 5 card. I know what A is, I said to myself. I know what it is for, but what else is it? Well, it’s ink on paper, that which is used to write lines. Pictures are made of lines, too. Images are sometimes words strung together to make a line. And lines are sometimes titles of poems. Now, what if I had a whole bunch of minimalistic pictures with which to work, things I could approach like I once saw Collins do with the cipher 5 and that he probably had seen Merrill and/or predecessors to Merrill do with other symbols? What if I turned the pictures, as if they were Chinese ideograms or hieroglyphs, into titles? What if I could imagine from airy titles concrete images, similar to the act of assembling boxes in my head when my brother Ted gave me that spatial relationships test when I was a kid?

Time, like a mist, evaporated: the clock quit ticking; the calendar vanished. I knew what I had to do, living now in a lighthouse, searching through the “wrong end” of a telescope, which was the right end for me. I couldn’t force the poem out. It became my method, my responsibility, to wait, to stick with it, the image, until I saw it afresh, the hope being that through silence I could shape a new language—one that others could “understand” though I was the only one to speak it. “There can be no poetry without the personality of the poet,” says Stevens. And hadn’t I always thought that if I couldn’t write, I’d like to sculpt? At last I had arrived, ready to conjure from two-dimensional figures a third dimension, albeit metaphysical, the tools for doing so being experience and imagination, as always, but studying each object with a new and intense appreciation for its form to settle on a trope. I will approach each in its natural order, I resolved. They will be like ekphrasis, art about art. I will translate. I will interpret. But I won’t explain. One cannot explain what is up to readers to sense. I can only suggest. I can only facilitate perception. Not alone will I make the invisible visible. And I shall try to make, when imagination allows, in tandem with the reader’s eye, the inaudible audible: bpj.org/poems/elder_alphaimages.html.

“Slow down for poetry,” Mark Strand admonishes in a 1991 New York Times Book Review essay (with a hilarious beginning I won’t spoil here). Yes, one must become one’s own flagman. In truth, often it is wise to simply pull over and park.

1. Wallace Stevens's grave.

2. The Stevens Walk.

3. Granite marker engraved with one of the "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird."

4. First edition of Divine Comedies containing James Merrill's inked-in corrections.

5. Karl Elder with Billy Collins.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this conversation, you might also be interested in our interview with literary critic Mark Athitakis about trends in American fiction and book reviewing, or our interview with novelist Hal Duncan about speculative fiction.

Looking for poetry ideas for your own writing? Visit our writing prompts section.

Return from the conversation about language poetry to the Creative Writing Ideas blog..

<< BACK from Conversation about Language Poetry to Creative Writing Now Home