How to Write a Novel

Here, you'll find a step-by-step guide on how to write a novel, including answers to questions like:

- How long should your novel be?

- How can you tell if your idea will work as a novel—or if it would be better as a short story?

- How do you divide a novel into chapters?

- Do you REALLY have to make a novel outline?

- How do you actually write the thing?

How to Write a Novel - Skip to Topic

- Step 1. Develop your idea

- Step 2. Check your idea

- Step 3. Do your research

- Step 4. Plan your novel

- Step 5. Make a schedule

- Step 6. Write a first draft

- Step 7. Revise and edit

- Step 8. Publish your novel

- Tips on how to write a novel

- More on how to write a novel

1. Develop an idea.

A good first step is to decide what kind of novel you want to write.

Here are some common novel genres, and how to develop a story idea for each of them.

1. Romance

In a typical romance plot, two people fall in love but must overcome problems or obstacles to be together. Most romance novels have happy endings.

To develop a romance novel idea, come up with:

- two characters who will fall in love.

- the main problem or obstacle in the path of their relationship (example: one of them is engaged to someone else).

- a situation that will keep them together long enough to work through the problem (example: they're working together to solve a crime.)

2. Mystery

In a typical mystery plot, someone investigates a crime to figure out who did it.

To develop a mystery novel idea, imagine:

- a crime, probably a murder. Think about interesting ways that the crime might have been committed and what clues might reveal who did it.

- a main character who has a reason to investigate the crime. This reason might be professional (e.g., the character is a homicide detective), or it might be personal (e.g., the victim is the main character's brother).

- some false theories that the main character might form before reaching the correct solution—and tricky false clues that point in the wrong direction.

3. Thriller/suspense

In thriller or suspense novels, the story is driven by danger, tension, and high stakes. There is often a main character who faces significant threats, either physical or psychological.

To develop a thriller or suspense novel idea, consider:

- a threat facing your character or others (e.g., a serial killer or an international conspiracy)

- why your character is the person who must stop the threat

- how your character will try to deal with the threat

- optional: something that creates time pressure on your character (e.g., in 24 hours the bomb will explode).

4. Science fiction

Science fiction often explores imaginative scenarios that are rooted in existing science and technology. Science fiction novels often answer the question "What if...?" This question is a good starting point for science fiction ideas.

Also consider:

- a setting that's different from our current world (like a distant planet, a future Earth, or an alternate dimension), or...

- a hypothetical scientific or technological development (for example, a machine that allows people to live forever).

- how this setting or technology will challenge your main character.

5. Fantasy

Fantasy novels are set in magical worlds or in a version of our world where magic exists. These stories often center around a protagonist on a transformative journey.

For your fantasy novel idea, consider:

- a magical setting (either a new world, or version of our own with magical elements).

- a main character with a special ability or destiny.

- a central conflict or quest that drives your character's story, challenging them and shaping their journey (for instance, the quest to defeat a dark wizard, or the search for a magical object that will save the world from a threat).

6. Horror

Horror novels are designed to scare or unsettle readers, and often involve supernatural elements or psychological suspense.

For a horror novel concept, you might imagine:

- a setting that provokes fear or unease (such as a haunted house or an isolated village).

- a source of terror, which could be supernatural (like ghosts or monsters) or more realistic (like a serial killer).

- a situation that will force your characters to confront this source of terror.

7. Literary fiction

In literary fiction, the focus is often on character development, as well as beautiful language.

To come up with an idea for literary fiction:

- you can start by imagining an interesting, three-dimensional character...

- then think of a situation that will put pressure on the character, forcing them change or revealing their hidden layers.

2. Check your idea.

Will your idea work as a novel?

Check or develop your idea to make sure that it includes:

- a main character or characters

- a main problem or challenge facing the main character(s).

Then, try this quick exercise...

Set a timer for 10 minutes and quickly make a list of possible scenes that you might include in the story.

Write each scene idea in just a few words; e.g., "Cinderella meets the Fairy Godmother", or "Cinderella the prince fight about politics".

Don't be picky—this is just brainstorming. Write down whatever comes to mind.

At the end of the 10 minutes look at your list and cross out any scenes that definitely DON'T belong in the story.

Then count how many are left.

You should have easily been able to come up with at least 15-20 ideas for scenes. If not, your story idea might not produce enough material for a novel.

In that case, you might turn it into a short story instead.

Keep in mind that a finished novel is likely to have more than 60 scenes!

A typical length for a novel is 80,000-90,000 words. Fantasy novels tend to run longer (epic fantasy can go over 100,000 words), while series romance and young adult might be a bit shorter.

For most genres, a novel may be easier to publish if you avoid going under 70,000 words or much over 100,000 words. But this is just a general guideline, and it might not apply to every story.

3. Do your research.

Why do research for a novel?

- to get ideas

- to give your fiction the texture of reality

- to avoid factual mistakes that can interrupt readers' suspension of disbelief.

For certain kinds of fiction, the need for research is more obvious. If you're writing historical fiction, you'll need to research your time period to get the details right. For crime fiction, you might have to research police procedures, ballistics, etc. For any novel set in a real place, you'll want to get the street names right.

But even if you're writing fantasy set in an imaginary world, research can be a source of ideas and make your world more believable. For example, you might decide to base aspects of your fantasy kingdom on Medieval Europe. Or, if you're writing science fiction, you might have to learn about existing science in order to imagine believable future developments.

You can do research at any stage of the novel-writing process. You might decide to do some research early on to generate story ideas. Or, you might save most of your research until you've written a rough draft and know exactly what information to look for.

4. Plan your novel.

A traditional story plot is based around a character's struggle to overcome a problem or reach a goal.

Every scene in your story should generally serve one of two purposes:

- move the character closer to, or further away from, solving the problem or reaching their goal.

- deepen the reader's understanding of the character and their situation.

Some authors begin with just a general idea of story plot and start writing without knowing exactly where the story's headed. For them, the first draft of a novel is a process of exploration.

Other authors like to do more advance planning before starting on a draft.

Investing more time in planning up front can make writing faster and mean less rewriting later on.

Novel Outlines

A novel outline doesn't have to be complicated. It can just be a list of scenes and order they happen in.

For example:

- Karen argues with parents about going to Joan's party.

- Vampires attack Joan's family and take over her house.

- That night, Karen sneaks out of her bedroom and heads to party.

An easy way to make a novel outline is to write scene ideas on separate notecards. Then you can play with order of the cards, adding scenes to fill in gaps, and taking out scenes that don't fit.

Once you come up with a sequence of scenes you like, copy that down, and you have an outline. It's that easy.

Click here for more novel-planning ideas.

Should you outline or not? It's not a life-or-death decision either way.

If you start without an outline and feel lost, you can stop and brainstorm some scene ideas to keep you going. You can go back and outline at any point in the writing process.

On the other hand, if you begin with an outline, you're not stuck with it. When new ideas occur to you, you can explore them. You can update the outline if you want or leave it behind.

Other tools for planning a novel...

Writer's Journals

Many authors keep notebooks where they jot down ideas, including descriptive details, fragments of dialogue, possible plot points, etc.

Character Profiles

To help you imagine important characters, you can create character profiles where you take notes on the character's physical appearance, background, and personality traits. Click here for a questionnaire you can use for your character profiles.

Pictures

You can collect pictures that help you imagine your characters and settings. You might search for these pictures online, cut them out of magazines, or draw them yourself.

Concept Words

The novelist Alexandra Sokoloff makes list of words that express the flavor, theme, or feeling of the novel she wants to write. For example, for her ghost story, THE HARROWING, Sokoloff's list included words like "shattered", "alone", "portal", "door", and "abandoned".

Timelines

It can be helpful to make a timeline of key events in your story. This is especially useful for historical novels, where you need to match the timing of plot points with historical dates. Timelines can also be essential in planning a detective novel, where the exact timing of characters' actions becomes crucial.

Setting Maps

It's sometimes helpful to draw a floor plan of an important house or building in a story. Fantasy writers often draw maps of the imaginary countries or worlds where their stories take place.

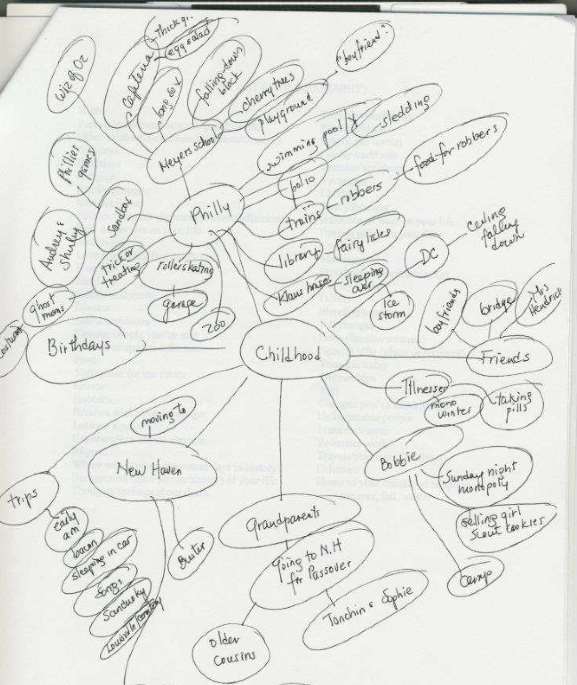

Mind Maps

You can brainstorm with visual idea maps like this one:

5. Make a writing schedule.

Writing a novel's a big project. If you leave the writing for when you happen to have a free moment, it's not likely to get done.

You need a plan. For example, maybe you can make writing time by waking up half an hour earlier every day. It's okay if you can only write for a short time each day; the key is to be consistent.

Imagine you write just half a page per day. If you do that every day, in one year, you can finish a draft of your novel!

6. Start writing!

You don't have to write the beginning of your novel first. You can write the novel in any order.

The building blocks of a novel are scenes. In scenes, you SHOW your story's events, instead of just summarizing them.

Summary and scene

Here's an example of summary:

John asked Maria to marry him. She said yes.

Here's the same event shown as a scene:

John stopped in the middle of the sidewalk, and Maria stopped walking too. "Maria," he said, "there's something I've been wanting to say to you. I know we've only known each other a short time, but—these last few days, they've meant a lot to me." She nodded, her face solemn. The sunlight lit the edges of her hair. He couldn't tell what she was thinking. He felt sweat begin to trickle down his back. Go on, he told himself—if you don't say it now, you might not have another chance. "This might sound crazy," he said, "and I don't have a ring or anything, but will you marry me?"

A bicyclist came speeding toward them, and they both stepped out of the way. John suddenly felt sure he'd made a terrible mistake. Of course she would say no, it had been crazy to ask. "Maria--" he said.

"Yes," she said.

"What?"

"Yes, I'll marry you."

Unlike a summary, a scene shows an event in what feels like real time. A scene happens in a specific place (in this case, a sunny sidewalk), and is normally shown from the point of view of a specific character (in this case, John). It is likely to include action and dialogue and descriptive details.

You'll generally want to show important events of your story as scenes. Then you can link the scenes together with summary and transitions; for example:

- "Later the same day..."

- "A whole week passed before he saw her again."

To write a scene:

1) Decide which character's point of view the scene will be written in. This is like the camera angle of the movie. Everything in the scene will be shown from that character's perspective. You can also show that character's thoughts (but no one else's!).

2) Imagine you are that character, experiencing an event from your story. Daydream the experience as vividly as possible, including sights, sounds, smells, and physical sensations. Try to capture that daydream on the page.

During your rough draft, don't worry too much about choosing the right words. You'll improve the wording later, during the revision stage.

Instead, try to lose yourself in the daydream of the story. If you do, the right words will often come on their own.

Scenes versus chapters

Most novels are divided into chapters. Chapter breaks give readers places to pause in their reading.

There are no rules for how long chapters should be or how to divide them. Authors often choose to end a chapter at a natural stopping point in a story, which is likely to coincide with the end of a scene. The same chapter may contain more than one scene.

Other times, an author might choose to end a chapter in the middle of a scene in order to create suspense. This is called a "cliffhanger". You interrupt the reader at an exciting moment, and the reader wants to turn the page to find out what will happen.

My advice is not to worry too much about chapter breaks while you're writing your rough draft. During the revision stage, you can figure out the best way to divide your novel into chapters.

This is often a process of trial and error. Experiment with breaking chapters in different places and see what works best.

The location of chapter breaks will affect the pacing or rhythm of people's reading experience. In general, shorter chapters make the story feel faster, and longer chapters slow it down.

7. Revise your novel.

Once you finish a rough draft, the first important step is to celebrate. WOW! What an accomplishment! You did it!

At this point, you can officially call yourself a novelist.

Give yourself a week, or even a month, to bask in the feeling of accomplishment. Then, it's time to start revising.

Revision is fun because you get to watch your novel getting better and better.

During the revision, I'd suggest starting with bigger, structural issues, and then working your way down to the fine points. It doesn't make sense to spend hours polishing a sentence if you're going to decide later to cut the whole chapter!

Click here to get a detailed checklist for revising your novel.

8. Publish your novel.

Once your manuscript is complete and revised, it’s time to think about publishing!

Traditional Publishing Options

Larger publishers normally require authors to submit through literary agents. So if you want to submit to major publishing houses, you will probably need to get an agent first. You can find a directory of literary agents here.

A reputable literary agent will not charge you anything upfront. Instead, they work on commission. For this reason, literary agents will generally only take on projects that look profitable. Getting a literary agent can be as challenging as finding a publisher.

Small publishing houses and university presses often allow authors to submit to them directly. You can find a directory of small presses here.

Before preparing your submission, visit the agency or publisher's website to check their author guidelines. They will tell you how they want you to submit to them.

Enter your email below, and we'll send you a free guide on how to publish a novel.

Self-Publishing

Another option is to self-publish your novel, as an ebook and/or print book. Jane Friedman offers a detailed online guide to self-publishing.

Tips on how to write a novel

1) Write a one-sentence summary.

Try summarizing your story plot in one sentence, including the main character and the main story conflict. Imagine you're writing the blurb on the book jacket.

If you can't boil your story down to one sentence, your ideas might not be focused enough yet.

2) Know what you write.

Creative writing teachers often say to "Write what you know" to take advantage of your personal experience. That's a good strategy, but you can also take a different approach and *write what you want to find out about*.

Use research and your imagination to write convincingly about things you've never experienced firsthand.

3) Make your readers care.

The easiest way to make readers care about your novel? The secret isn't to write about "important" themes such as war and death. The news of someone's death doesn't matter to most people unless it's someone they know. So, the secret is to create a character that feels to readers like a real person that they know. Then create a situation where your character has a lot at stake.

Maybe the character is in danger of losing their job, or they've met the love of their life, or they are trying to save up to buy a sports car. The situation doesn't have to be "important" in an objective way, as long as it's important to the character.

4) Don't include everything you know.

The more information you know about your characters and the setting of your novel, the more real you can make these for your reader. But your reader doesn't want to read a complete biographical profile of every character or census report on the town where the novel takes place. If you keep all this information in your head, you'll be able to use the right details at the right moment. And readers will have a sense of a reality that extends beyond the edges of the page.

5) Show key events as scenes.

Some information is better summarized. Does your character, Jane, come from a long line of doctors? It's probably okay to summarize this in one sentence, instead of following each one of them day-by-day through medical school (unless that's supposed to be the subject of your novel). But if your novel is about Jane's marital problems, and Jane finally decides to confess to her husband about her affair, your reader wants to see and hear that confrontation.

Don't just mention that Jane makes a confession. Show the reader what she says. Show what her husband answers. Show their body language. Show their daughter walking in on the fight. Show the orange juice stain on the wall after Jane throws her glass across the room.

6) Don't push your characters around.

At every moment, ask yourself, "What would this character do?" "What would happen next?" And be true to the answers.

If your character is someone who go to bed and cry quietly after a fight, don't have her scream and smash things instead just because your plot outline requires it. Don't force things to happen because you want your novel to go in a specific direction. If you do, your readers will notice.

Hemingway said that every writer needed a b.s. detector. Make sure that yours is working overtime.

What if you have a rebellious character who doesn't want to take the path you have planned for them? In this situation, you have two options. Either fire that character and rewrite your novel with a new one, or choose a different path for your plot.

How to Write a Novel - More Resources

- How to get creative writing ideas

- Novel structure

- Plot structure

- How to write a novel beginning

- How to complicate your plot

- How to write a novel ending

- FAQ on how to write a novel

- Elements of a novel

- Types of novels

- How to write a mystery

- Suspense writing techniques

- How to write a thriller

- How to write science fiction

- How to write fantasy

- How to write romance

- How to write historical fiction

- More on writing historical fiction

- Types of narrators

- Verb tenses in fiction

- Novel-writing software

- How to write a novel using the Snowflake Method